Burlesque isn’t just fishnet stockings and feathers. It’s a living archive of resistance, a space where women, trans folks, and nonbinary performers reclaimed control over their bodies when society told them to stay quiet. In the 1940s, strippers were arrested for dancing in public. In the 1990s, they were erased from feminist discourse. Today, burlesque performers are writing textbooks, testifying in court, and leading workshops on consent and labor rights. This isn’t entertainment as distraction-it’s politics in motion. And it’s not happening in some underground club in New York. It’s happening in basements in Brisbane, community centers in Melbourne, and stages in Newcastle, where performers turn spotlight glare into a mirror for systemic change.

Some people confuse burlesque with erotic massage dubai, but the difference matters. One is a transactional, private encounter; the other is a public, collaborative act of storytelling. Burlesque doesn’t sell access to the body-it sells the idea that the body can speak, defy, and demand dignity without permission. When a performer lip-syncs to a pop song about empowerment while peeling off a sequined glove, they’re not just dancing. They’re rewriting the rules of who gets to be seen, who gets to be desired, and who gets to decide what that desire looks like.

The Roots: From Vaudeville to Vice

Burlesque started in the 1860s as a parody of highbrow theater. Women in tights mocked opera singers and politicians. By the 1920s, it had shifted. The focus wasn’t just on satire-it was on the body itself. Performers like Gypsy Rose Lee turned striptease into an art of suspense, not exposure. She didn’t take off her clothes to titillate. She took them off to prove she could control the gaze. The industry boomed until the 1950s, when moral panic led to crackdowns. Clubs were shut down. Performers were labeled immoral. Many were forced into sex work just to survive.

That’s where the feminist debate began. Mainstream feminism in the 1970s often dismissed strippers as victims, not agents. But sex worker feminists like Carol Leigh and Annie Sprinkle pushed back. They argued: if you believe in bodily autonomy, you can’t pick and choose which bodies deserve respect. A stripper isn’t less feminist because she takes off her clothes. She’s more feminist if she chooses to, on her own terms.

The Theory: Why Burlesque Is Feminist

Sex worker feminism doesn’t see sex work as inherently oppressive. It sees oppression in the laws, stigma, and violence that surround it. Burlesque, then, becomes a tool to challenge those systems. Performers use humor, exaggeration, and theatricality to expose how society objectifies women while pretending to protect them. A routine where a performer slowly removes a suit of armor made of bras and panties isn’t just funny-it’s a metaphor for shedding societal expectations.

Academic work by scholars like Dr. Amy H. Stoller and Dr. Laura Kipnis shows that burlesque audiences aren’t just men looking for arousal. They’re students, nurses, retirees, queer teens, and former sex workers. The crowd doesn’t come to consume-they come to witness. And witnessing is political. When someone in the front row sees a performer who looks like their mother, their sister, or themselves, and laughs with genuine joy, it breaks the myth that sex work is shameful.

The Voices: Three Performers, Three Stories

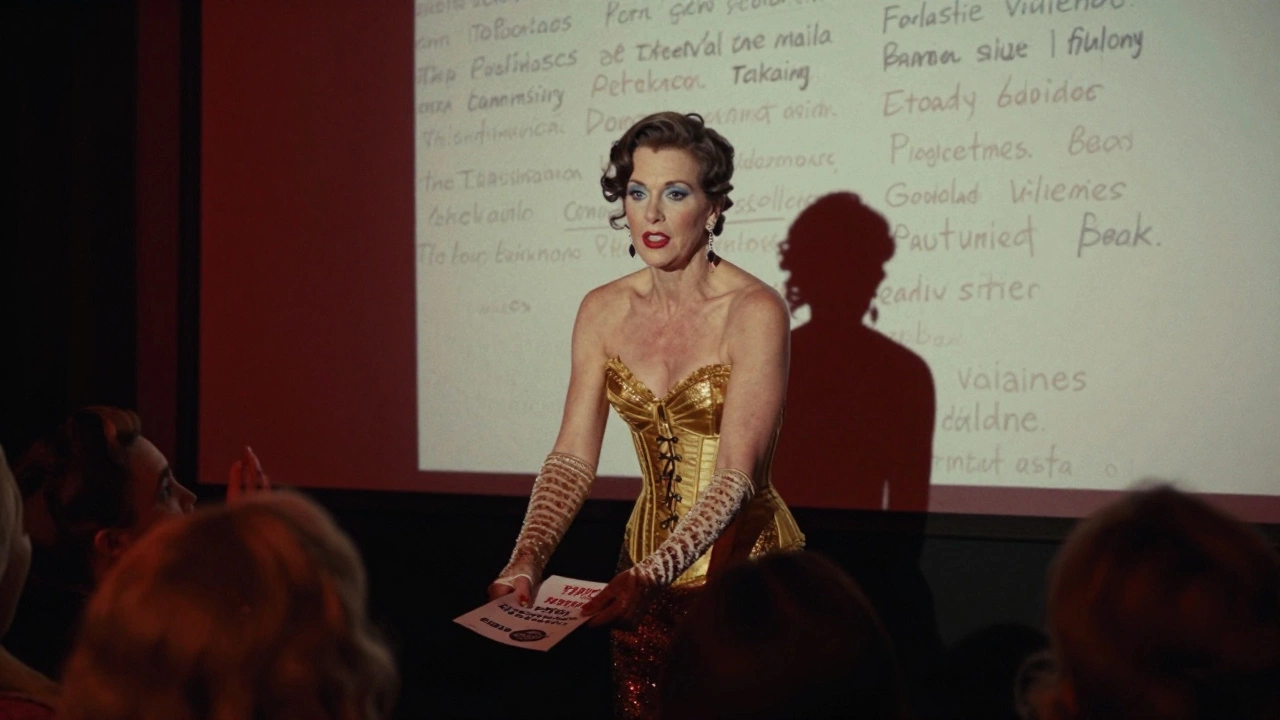

Meet Rhea Bell, 38, who started performing in Sydney after leaving an abusive relationship. She uses burlesque to rebuild her sense of safety. "I used to think my body was a problem," she says. "Now it’s my stage. Every time I step into a corset, I’m saying: I’m not broken. I’m built." Her act, "The Last Lingerie," ends with her handing out pamphlets on domestic violence hotlines to the audience.

Then there’s Juno Vega, a nonbinary performer from Adelaide who blends drag, circus, and burlesque. Juno’s act, "Bureaucracy of Desire," involves filling out fake government forms that ask, "Why do you deserve to exist?" Each form is stamped with a red seal: "Approved by the People." Juno doesn’t perform for men. They perform for anyone who’s ever been told they’re too much or not enough.

And there’s Tasha Monroe, 51, a former nurse who started burlesque after retirement. "I didn’t want to fade away," she says. Her act, "Nurse’s Notes," is a parody of hospital paperwork-where she "prescribes" herself confidence, pleasure, and freedom. She’s performed in nursing homes, libraries, and even a local council meeting. "They thought I was there to entertain," she laughs. "I was there to remind them that older women still have bodies, still have power."

Legal Battles and Local Wins

In 2023, a burlesque performer in Perth was charged with indecency for wearing a feathered pasty that covered less than a postage stamp. The case went to the Supreme Court. The judge ruled: "The law does not criminalize art because it is sexually suggestive. It criminalizes harm. No harm was shown." That ruling changed how police handle burlesque events across Australia.

Now, cities like Melbourne and Canberra have designated burlesque zones-areas where performers can operate without fear of licensing harassment. The Australian Burlesque Collective, formed in 2020, now has over 400 members. They offer legal aid, mental health support, and even body-to-body massage workshops for performers dealing with chronic pain from years of corsetry and high heels. These aren’t spa treatments. They’re occupational therapy for artists who’ve been told their work isn’t real labor.

Why This Matters Now

As global movements roll back reproductive rights and gender-affirming care, burlesque becomes even more vital. It’s a rehearsal space for freedom. It teaches people how to claim space in a world that wants them small. It shows kids that bodies aren’t shameful-they’re stories. And it reminds adults that dignity doesn’t come from modesty. It comes from choice.

Some critics say burlesque normalizes exploitation. But the real exploitation isn’t in the performance. It’s in the silence. In the laws that make it illegal to dance in public without a permit. In the landlords who refuse to rent to performers. In the banks that freeze accounts because of "adult content." Burlesque fights back by refusing to hide.

When you see a performer on stage, don’t ask if they’re "really" feminist. Ask: what are they fighting for? What are they refusing to give up? What are they teaching the next generation? The answer is always the same: autonomy. Joy. Power.

What Comes Next

Burlesque is no longer just performance. It’s activism. It’s education. It’s community care. In 2025, universities in Sydney and Melbourne now offer credit courses on burlesque as social practice. Performers are invited to speak at human rights panels. A documentary on Australian burlesque won Best Documentary at the Melbourne International Film Festival last year.

The future isn’t about getting mainstream approval. It’s about building systems that don’t require it. Safe venues. Fair pay. Legal protection. Mental health funding. And yes-body-to-body massage, offered by trained performers for performers, because the body is not just a tool for art. It’s the artist itself.

There’s no single definition of feminism. But if feminism means the right to exist fully, loudly, and unapologetically in your body-then burlesque isn’t just part of it. It’s one of its loudest voices.